|

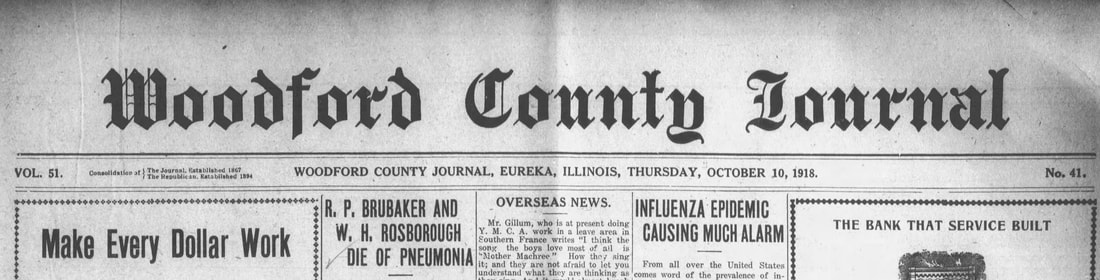

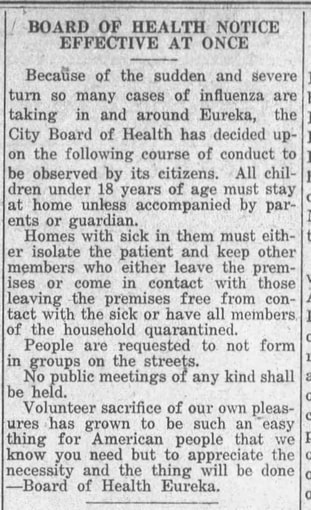

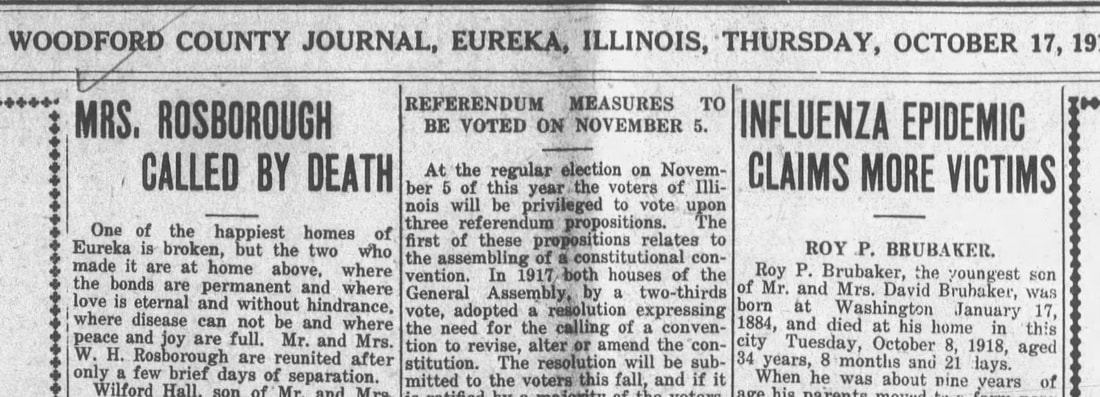

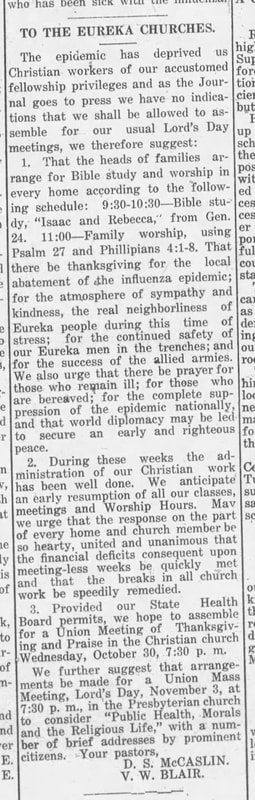

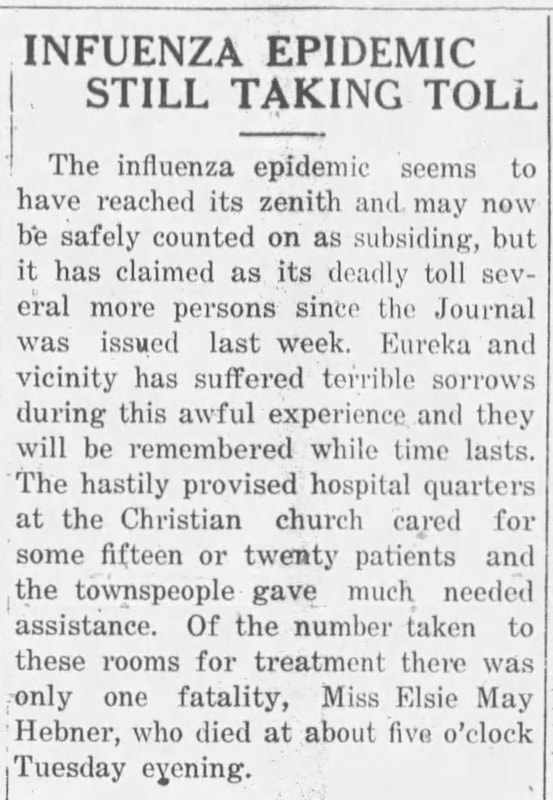

In the midst of our own pandemic experience, I was curious to look back and see how Eureka fared in 1918 when the Spanish Influenza struck our town. Using digitized issues of the Woodford County Journal [hereafter referred to as the Journal] and the Pantagraph, this blog pieces together what was reported for the Eureka community. You can access the historical archives of both newspapers for free through Newspapers.com on the library’s public computers when we are open. For a firsthand account, please see 1918 influenza survivor Anna McCloud’s story which was recently published in the Peoria Journal Star: https://www.pjstar.com/news/20200411/luciano-eureka-woman-already-survived-viral-pandemic---more-than-century-ago. In 1918 we were in the midst of World War I. The Journal regularly featured overseas news, letters from soldiers, and reports on local war efforts such as gasless Sundays, reducing waste, and donating nut shells and fruit pits for the manufacture of carbon for gas mask respirators. There was regular mention of pneumonia as a cause of death throughout the winter of 1917 – 1918, but it does not seem to be connected to any widespread pandemic. There was a report in the February 7 edition of the Journal of the death of Eureka soldier Henry William Jennings at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station Hospital of pneumonia on February 6. The Pantagraph noted the increase of pneumonia in the national army on March 29, 1918, and in July word spread of the influenza impacting the German army. The influenza gained widespread public attention in the fall of 1918 as it spread through the United States’ military camps. On August 17, 1918, the Pantagraph first used the term “Spanish Influenza” and reported that the New York City Department of Health warned against kissing “except thru a handkerchief.” The Journal, a weekly paper printed every Thursday as it is today, mentioned a relative of a Eureka family ill with pneumonia at Camp Custer, Michigan, on August 22. Throughout September, the Pantagraph continued to report daily on the number of cases quickly growing throughout the nation at both military camps and in cities. Of particular interest was the status of the Great Lakes Naval Training Station north of Chicago and Camp Grant in Rockford as many area soldiers were stationed there. On September 23 the paper reported that the influenza appeared at Great Lakes on September 9, peaked around September 19, and was now decreasing. September was also reportedly the coldest September on record. By late September and early October, the influenza was spreading rapidly through central Illinois. On October 1, the Pantagraph reported an outbreak in the town of Forrest in McLean County. At that time Forrest had 250 cases, three dead, and their schools and public places were closed. On October 5, Peoria reportedly had 22 cases. On October 7, Bloomington had 47 cases and Normal had 4 cases. On October 8 the Pantagraph printed a directive from the United States Surgeon General recommending all schools, places of amusement, and public meetings discontinued “in all places where the malady becomes prevalent.” Turning to Eureka, the September 27 issue of the Journal makes no mention of the influenza. Unfortunately, there is a gap in our knowledge of what happened the next week as the October 3, 1918, edition has not been microfilmed or digitized. The next available edition is the following Thursday, October 10. By then, the pandemic was the leading headline as residents were beginning to succumb: “R. P. Brubaker and W. H. Rosborough Die of Pneumonia” and “Influenza Epidemic Causing Much Alarm.” Between September 27 and October 10, the pandemic hit the town and was spreading. By October 10, Eureka and the surrounding townships reportedly had over 100 cases – often affecting whole families at the same time. Schools, churches, and the movie theater were closed and public gatherings were prohibited in Eureka. The October 10 Journal mentions that “With so many doctors having gone into the army service, the people cannot get the medical assistance they should have.” Community leaders were discussing relief work to help families affected, and the county chapter of the American Red Cross issued a call for volunteers to make relief calls and provide meals to families. There was also a call for all with medical training to volunteer. The City Board of Health issued rules to be followed: During the month of October, the Journal reported a total of 10 deaths in the city. Nine of the ten victims were young – ranging in age between 13 and 34. Four of the deaths were husband and wife couples. The deaths of Wilfred H. and Viola Rosborough, ages 28 and 24 respectively, were especially tragic as the couple left behind a two-week-old baby daughter. The couple died within five days of each other. Wilfred was a partner with Merle Wright in the firm Wright & Rosborough – undertakers and furniture dealers. The second married couple was Geraldine and Howard Glasgow. Their deaths, a week apart from each other, left behind two young children. Mr. Glasgow worked at Dickinson and Company. Eureka College had over 60 cases of influenza according to the October 17 edition of the Journal. Unfortunately, one Eureka College student was among the dead reported in October – Tobias Bilyeu. Bilyeu attended Eureka College between 1916 and 1918 for his freshman and sophomore years as a ministry student. In the fall of 1918, he was member of the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) and was eager to enlist for service. Bilyeu fell ill on Sunday, October 6. Within a day of falling ill, he developed pneumonia and was removed from the hospital wing of the barracks to the home of President Pritchard. On Wednesday he was moved to the Harris home. The Harris home featured a ground floor room where he could be watched over by two trained nurses. He passed away at the Harris home on Friday, October 11. Another death in Eureka associated with the college was Mrs. Carrie Merriman. Merriman was from Williamsonville, Illinois, and came to Eureka to take care of her son Robert, a student at Eureka College who was ill from influenza. She became sick within days of her arrival and passed away here on October 16. Her son recovered. As churches were unable to hold services, they encouraged families to gather for meditation and prayer in their homes at the normal time for church services. Pastor McCaslin of the Presbyterian Church published the scripture to be read in the October 10 edition of the Journal (Psalms 91 in case you are curious). In the October 24 and 31 editions of the Journal, the ministers of the Eureka Christian Church and the Presbyterian Church together published a proposed schedule for home worship with specific Bible verses and prayers recommended. The Eureka Christian Church, of which at least six of the ten who died were members, also became a temporary community hospital. In the October 24 edition of the Journal, the following article was printed: The total number of those who were taken ill, but recovered, in Eureka was not reported in the Journal but likely numbered in the hundreds. In the October 17 edition of the Journal it was reported that Chicago had 17,943 cases and 2,264 deaths to date, Peoria had 10,000 cases, and Bloomington had 1,200 cases and 11 deaths. The Journal also reported that the City of Eureka passed an ordinance creating the position of Health Commissioner. The new position, with the approval of the Health Department, would oversee and have “supreme authority” over quarantine issues. The State Board of Health was trying to quickly disseminate information about the disease through ministers, movie theaters, factory owners, and newspapers. The focus of the information campaign was on how the influenza was being spread and how to treat it. One warning in the October 17 edition was to be “On guard against the careless sneezer, cougher, and spitter, because such persons are largely responsible for the widespread epidemic of influenza . . .. ”

By October 31, the flu was “on its last legs” in Eureka. Public gatherings resumed and churches, schools, and the movie theater opened in Eureka sometime between October 31 and November 7. A general election was held on November 5 and was the focus of the front-page headlines for both the October 31 and November 7 editions of the Journal. Although gatherings were permitted, those with illness in their homes were prohibited from attending. In addition, a doctor was required to evaluate all students daily at the reopened schools. The regular presence of the doctor (Dr. Banta) led to discussion of hiring a permanent nurse for the schools according to the December 12 edition of the Journal. Ms. Belle Leeds was hired as the first supervising school nurse by December of 1918. Despite the lifting of the quarantine, the influenza was not completely eliminated. Roanoke continued to suffer through November and totaled at least 19 deaths by November 28. The Journal continued to report smaller flare-ups and deaths in Eureka and other parts of Woodford County. There were two additional deaths in Eureka by December 31, 1918. It is impossible to say for sure whether the pneumonia deaths that continued through April 1919 were due to the Spanish Influenza or to the regular flu season. In the July 24, 1919, edition of the Journal it was stated that there were 89 Spanish Influenza deaths total in Woodford County in 1918. LaSalle County had 563 deaths, McLean County had 248, Livingston County had 123, and Marshall County had 36. A recent article on Peoria’s 1918 pandemic states Peoria had 40 deaths. To read this article, visit http://www.peoriapubliclibrary.org/peoria-s-1918-spanish-flu-terror. For an article Bloomington-Normal during the pandemic, visit https://bit.ly/3f6tdF6. Chicago had an estimated 8,510 deaths (https://www.chipublib.org/blogs/post/chicago-fought-to-limit-flus-spread-during-1918-epidemic/). The names of the ten Eureka victims in October 1918 are: Roy P. Brubaker (age 34), Wilfred H. Rosborough (age 28), Viola Rosborough (age 24), Geraldine Glasgow (age 23), Carrie Merriman (age 53), Tobias Bilyeu (age 25), Howard Glasgow (age 26), Lyford Bradle (age 14), Lynda Rush (age 32), and Elsie May Hebner (age 13). In addition to these local deaths, there was also sad news of at least one of Eureka’s soldiers dying of the disease. On October 17 the Journal reported the death of Claude Sharpe at Camp Hancock, Georgia. Sharpe had left Eureka for Camp Grant in Rockford in September. Camp Grant was one of the military camps suffering from an infuenza outbreak at the time. After a short stay, he was transferred to Camp Hancock where he developed symptoms and passed away. Sharpe is buried in Olio Cemetery along with the Rosboroughs, Glasgows, Roy Brubaker, Lyford Bradle, Lynda (Mrs. William) Rush, and Elsie Hebner. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorLibrarian Cindy O'Neill loves researching local history! She has extensive experience in historical research, genealogy, and archival resource management. She previously worked in the archaeology and museum fields and has Master's degrees in both history and library science. Recent local history projects include a history of the Eureka Pumpkin Festival, the creation of a digital archive of festival photos and memorabilia on the Illinois Digital Archives website, and an architectural history of the Eureka Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Archives

January 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed